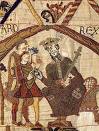

Whatever happened to provider capitation? It was going to be a core element in the managed care strategy to revolutionize healthcare delivery – back when people thought managed care could revolutionize healthcare delivery. In fact, capitation has been around in one form or another in every attempt at healthcare reform since the Norman Conquest. Some even say an earlier variant existed in ancient China. We don’t hear much about it anymore. Where has it gone?

When Henry I assumed the throne of the newly-combined kingdoms of England and Normandy he initiated a sweeping set of healthcare reforms. Historical documents indicate that soon thereafter at least one “physician,” “John of Essex,”was receiving an honorarium of one penny per day for his efforts. As historian Edward J. Kealey explains1, that sum was roughly equal to that paid to a footsoldier or a blind person. (Historically doctors haven’t always been the high earners they are today.)

I assume that John of Essex’s income was a form of “capitation” – that is, a flat payment for treating a fixed number of individuals whether they are ill or well. This is only an assumption, given the lack of better historical data, but I believe it’s a reasonable one.

There’s clearer historical evidence to suggest that American doctors in the mid-19th Century were receiving capitation-like payments. No less an authoritative figure than Mark Twain, in fact, is on record as saying that during his boyhood in Hannibal, MO his parents paid the local doctor $25/year for taking care of the entire family regardless of their state of health2. That’s genuine capitation.

The reason why capitation payments made a comeback in the managed care field during the 1980’s is because fee-for-service medicine creates perverse incentives for physicians. As many people now understand, fee-for-service medicine pays doctors more for treating illnesses and injuries than it does for preventing them – or even for diagnosing them early and reducing the need for intensive treatment later.

That’s one of the reasons why I haven’t embraced “Medicare for all” as a meaningful model for healthcare reform. Most Medicare is provided on a fee-for-service basis, and our country has created a class of high-earning doctors under that system. Medicare attempts to control utilization as well as cost, but putting the entire population into the current Medicare system without addressing the fee-for-service issue could have unintended consequences.

Nevertheless, the managed care industry’s experience with capitation hasn’t been a good one. The 1980’s saw a number of HMO’s attempt to put physicians in independent practice, especially primary care physicians, into a capitation reimbursement model. The result was often negative for patients, who found that their doctors were far less willing to see them – and saw them for briefer visits – when they were receiving no additional income for their effort.

Attempts were also made to aggregate various types of health providers – including hospitals and physicians in multiple specialties – into “capitation groups” that were collectively responsible for delivering care to a defined patient group.

Americans aren’t collective people by nature, however, and these efforts tended to be too complicated to succeed. One lesson that these experiments taught is that provider behavior can’t be changed unless the relationship between that behavior and its consequences is fairly direct and easy to understand.

Still, fee-for-service medicine will pose a significant risk to any health reform effort. Does capitation play a role in reform? There are only four possible answers:

- No. The HMO experience taught us it can’t work in the U.S. context, so we need to stick with fee-for-service medicine.

- No. Only group model healthcare (e.g. Kaiser, the VA) can succeed in the U.S.

- Yes. The HMOs didn’t get it right.

- We don’t know. The topic warrants further discussion and research.

I’m going with #4. How about you?

As for the ancient Chinese, physicians such as Dong Feng treated people without charge in the Third Century AD3. I’ve heard it said that other Chinese physicians were only paid if their patients got well. But stories that the Emperors cut off the heads of their doctors if they failed to cure them are only legends, as far as I can tell.

In any case, that form of reimbursement is more commonly known as de-capitation.

1Medieval Medicus: A Social History of Anglo-Norman Medicine. Kealey, Edward J. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981.

2The Autobiography of Mark Twain. Clemens, Samuel (Charles Nieder, ed.) Perennial Classics (pub. date unknown.)

3Guo, Z. “Chinese Confucian Culture and the Medical Ethical Tradition.” J Med Ethics, 1995.